Location, Location, Location

Graduate Psychology Research at Queen’s University culminating to a published thesis “Sensorimotor Working Memory Capacity Limits” (2016).

The Experience

This research was conducted at Queen’s University, between 2014 -2016 as part of the requirements for completion of a Psychology M.Sc. Brain, Behaviour and Cognitive Science Specialization.

All experiments were conducted under the supervision of Dr. Randy Flanagan. Some of this research was previously written up by Stephanie Clayton (2016) towards completion of her undergraduate thesis.

Below, you can read an overview of the thesis or read the full paper here.

Learn more about the Action and Cognition Lab here.

SENSORIMOTOR WORKING MEMORY CAPACITY LIMITS (2016)

The Research

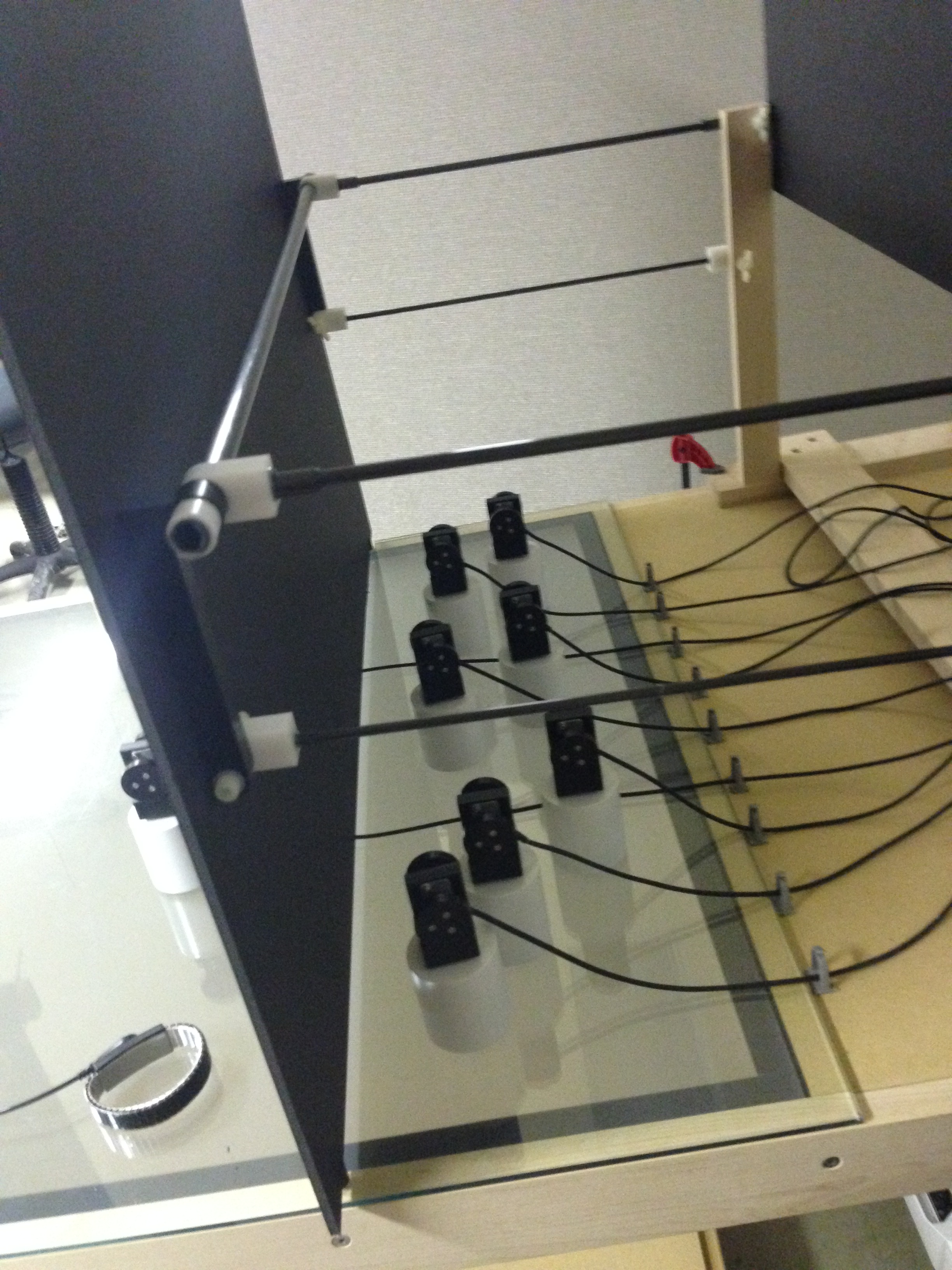

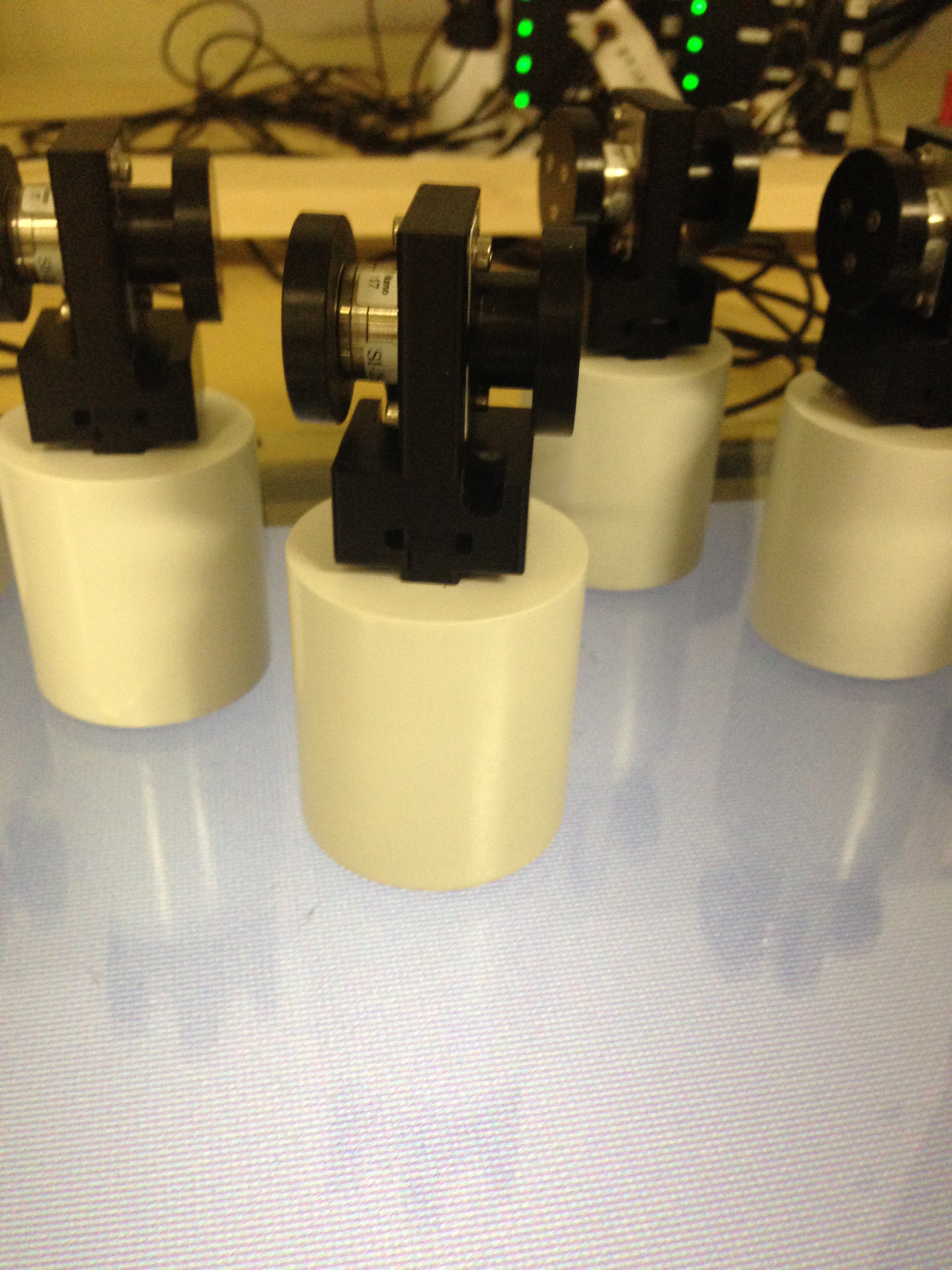

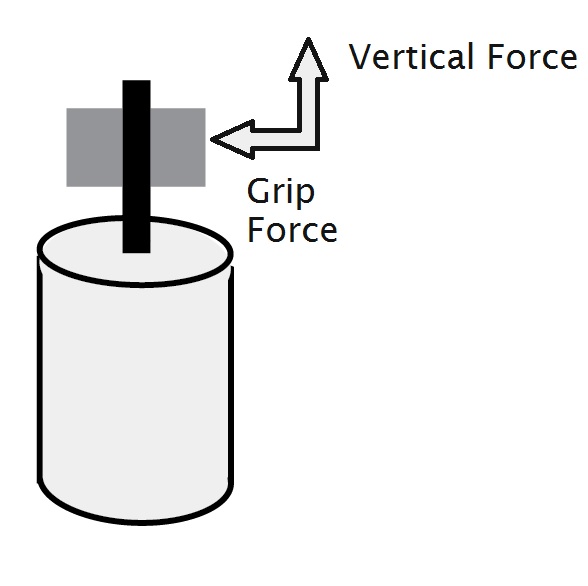

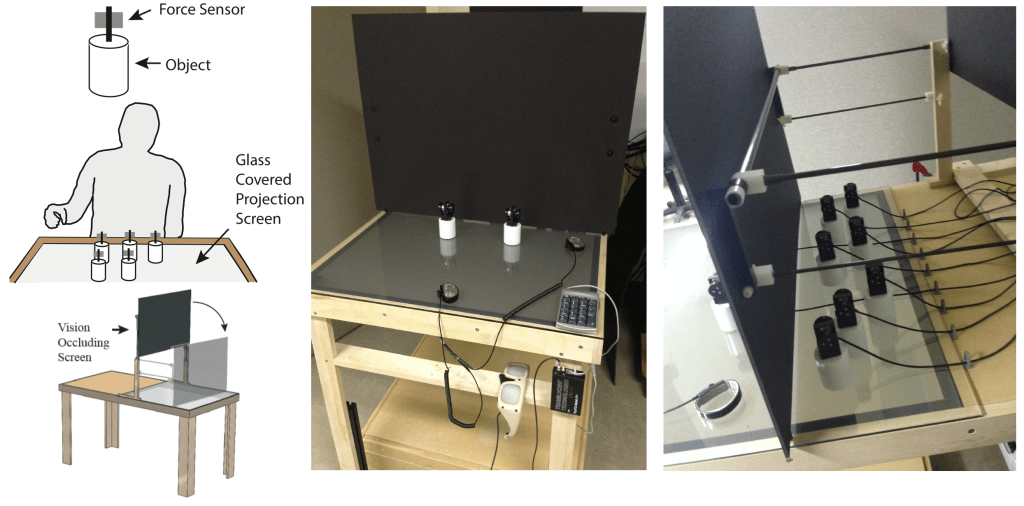

Two novel studies examining the capacity and characteristics of working memory for object weights, experienced through lifting, were completed. Both studies employed visually identical objects of varying weight and focused on memories linking object locations and weights. Whereas numerous studies have examined the capacity of visual working memory, the capacity of sensorimotor memory involved in motor control and object manipulation has not yet been explored. We assessed working memory for object weights using an explicit perceptual test and an implicit measure based on motor performance. The vertical lifting and the horizontal grip forces applied during lifts were used to assess participants’ ability to predict object weights.

In Experiment 1, participants were presented with sets of 3, 4, 5, 7 or 9 objects. They lifted each object in the set and then repeated this procedure 10 times with the objects lifted either in a fixed or random order. Sensorimotor memory was examined by assessing, as a function of object set size, how lifting forces changed across successive lifts of a given object. Force scaling for weight improved across the repetitions of lifts, and was better for smaller set sizes when compared to the larger set sizes, with the latter effect being clearest when objects were lifting in a random order. However, in general the observed force scaling was poorly scaled.

In Experiment 2, working memory was examined in two ways: by determining participants’ ability to detect a change in the weight of one of 3 to 6 objects lifted twice, and by simultaneously measuring the fingertip forces applied when lifting the objects. Even when presented with 6 objects, participants were extremely accurate in explicitly detecting which object changed weight. In addition, force scaling for object weight was generally quite weak and similar across set sizes. Thus, a capacity limit less than 6 was not found for either the explicit or implicit measures collected.

Movement is the only way we have of interacting with the world, whether manipulating objects, navigating through our environment, playing musical instruments, or communicating with others.

Thus, understanding how actions are planned and controlled, how actions are perceived by observers, and how skilled actions are learned, is an important enterprise.